As a person who is of a "certain age" I tend to read the obituaries looking for people who have not lasted as long as I have. It's not a morbid fascination. I am not concerned about dying. I am just interested in how they died, so I can be more careful that the same thing doesn't happen to me.

Just recently I noticed a particular obit in the NYT which caught my attention. The headline was: "Sister Frances Ann Carr, 89, One of Last Three Shakers." She had joined the Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village, in New Glouchester, Maine, in 1937. Her death leaves two surviving Shakers, Brother Arnold Hadd, 60, ad Sister June Carpenter, 78. Literally the end of an era.

I have had a long and personal relationship with Shakers, Shaker communities, furniture and their beliefs for most of my adult life. I first discovered their existence by reading antiques books in the 1960's and was intrigued by the perfect simplicity of their designs. When I created my first television series in 1973, "Welcome to the Past, the History of Antiques," I devoted an entire half hour show to the Shakers. To gather information for this show I travelled East to visit many of the existing Shaker communities. I consider Shaker furniture to be perhaps the only authentic American style of furniture, with designs transmitted by angels from heaven, not emigrants from other countries.

The term "Shaker Furniture" is not well understood and there are many examples of simple furniture identified or sold as "Shaker" which is not accurate. True Shaker furniture is extremely rare, as it was made by them for their use in their communities, which at their peak during the Civil War, reached a limit of 6,000 members. They preferred to be separate from the outside world, and kept these furnishings to themselves, with one exception. Robert Wagon, a Shaker in New York in the 1870's, operated a rocking chair company at Mt. Lebanon where he sold a range of sizes of rocking chairs, with woven tape seats. These were the only items of Shaker furniture sold outside the communities, until nearly a century later when Dr. Edward Deming Andrews and his wife, Faith, were invited to see objects in the private rooms at Hancock.

The story of how the Andrews "discovered" the Shakers is wonderful, and I encourage you to research it yourself. I only point out here that it was their first book that I discovered in the library so many years ago that made me aware of this wonderful sect.

In any event, I spent a lot of time and gas driving around to visit as many old Shaker communities as I could back in the early 1970's. It is during one of these trips I found myself in the Berkshires of Western Massachusetts arriving in Pittsfield. I knew the community of Hancock was just outside town and, since it was late in the day, I stopped in the local YMCA to clean up. I remember standing in the showers, enjoying the hot water after a long day on the road. As I was getting dressed one of the men in the locker room asked me where I was from. I told him I was traveling around visiting historic sites and intended to go to Hancock.

"Well, then," he replied, "I think you should meet Faith. I am the town postman and I know everyone in this place. She is on my route and I know she enjoys meeting students of the arts."

We walked up into the lobby and he got on the telephone. When she answered, he said "I have someone who wants to meet you." Then he handed me the phone.

I couldn't believe it. She immediately told me "Go to Hancock first, then come see me."

It was off season and the weather was brilliant for that time of year. I had the village of Hancock completely to myself. It had just finished raining and the sun was shining through the clouds, pouring through the open windows of the buildings. I was alone with the ghosts of the Shakers. There were no other visitors. After a few hours I felt a strange connection to the place. It was like I had lived there my whole life. There was a place for everything and everything was in its place.

The next day I visited Faith Andrews and we talked for hours. She invited me back the next time I was in the area and over the next few years I visited her many times, often staying in her spare bedroom. She was an amazing and distinguished woman, who took the time to educate me on many aspects of the Shaker philosophy which remain with me today. My wife, Kristen, made a stained glass window of the Tree of Life and I made a simple cherry frame. We presented it to her during one visit and she returned the gesture, giving me some personal Shaker items, which I may discuss in another post.

I do not intend to go more deeply into the history of the Shakers here, as you can do that for yourself. The point of this story relates to the recent passing of Sister Frances Ann.

On one of these visits with Faith she confided in me that there was something I could do to resolve a controversy among the surviving Shakers. It involved the remaining dozen or so Sisters who were rather evenly divided between Canterbury and Sabbathday Lake.

Here is the entry on this topic in Wikipedia:

In 1957, after "months of prayer", Eldresses Gertrude, Emma, and Ida, the leaders of the United Society of Believers and who were based out of Canterbury, voted to close the Shaker Covenant, the document which all new members need to sign to become members of the Shakers.[27] In 1988, speaking about the three men and women in their 20s and 30s who had joined the Shakers and were living in the Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village, Eldress Bertha Lindsay stated, "To become a Shaker you have to sign a legal document taking the necessary vows and that document, the official covenant, is locked up in our safe. Membership is closed forever."[27]

This was about 1978 when Faith asked me to run this errand. Since to adopt any member of the public into the Shaker faith it was required that a small group of both Brothers and Sisters approve the applicant, when the last Brother passed away (1957) the remaining Sisters voted that no new members would be accepted. That meant the end of the faith. The end of the Shakers.

It is important to mention that the Shakers held in trust millions of dollars of property. There is a certain interest to join the group just considering the value of the land. The Sisters at Canterbury were determined not to accept a new Brother, but the Sisters at Sabbathday Lake (including Sister Frances Ann) were open to the idea. They accepted Ted Johnson, a reformed preacher, as a "Brother" and he moved in with them, living, of course, in separate buildings. Now that they had both a Brother and Sister to accept new converts, they began rebuilding the community. These are the "three men and women in their 20's" mentioned in the Wikipedia entry above.

Faith had been communicating with Sister Gertrude and Eldress Bertha at Canterbury and they had decided to send me on a "mission." Faith handed me a sealed envelope and told me to go to Canterbury. When I got there I went on the little museum tour with all the other tourists. At the end of the tour, I was taken aside by the guide and escorted into the main residence kitchen. There I sat at a table with Sister Gertrude and Eldress Bertha eating a delicious tomato sandwich while they opened and read the letter from Faith.

I was instructed by them to travel to Sabbathday Lake and investigate as much as I could about these "new" Shakers and how the Sisters were being treated. I did as I was asked and, when I arrived at my destination I quietly asked how one became a Shaker and would it be possible for me to join? I had some interesting meetings with those in charge, did some exploring into places not open to the public, and generally looked around. To me it seemed to be a normal situation, and I reported back that I found nothing unusual. Except that there were Brothers.

I do not know if one of the Sisters I talked with was Sister Frances Ann. According to the NYT: "Sister Frances, like the other Shakers, always hoped new members would join the community and welcomed visitors." That was the feeling I got when I visited such a long time ago.

I wonder how my life would have changed if I had decided to stay. It was very appealing.

"It's a gift to be simple. It's a gift to be free. It's a gift to come down where you ought to be."

My life is not simple. However, I am free and I believe I am where I ought to be. Thank you, Faith.

A traditional furniture conservator, restorer and maker discusses his life experiences and his philosophy of work. If you love marquetry this is the place to discuss it. All work is done with hand tools and organic traditional materials and methods.

Monday, January 23, 2017

Tuesday, January 17, 2017

Got Glue?

|

| Curbside Delivery: A Ton of Glue! |

When I lecture about using glue for woodworking, I usually start in the 17th century. Although it is true that animal protein glues were used as early as the Egyptian times, traditional woodworkers in Europe up until the 17th century relied on mechanical fastening for their assembly.

First and most common were nails, which could be fashioned by the local iron worker, if you had the funds. If you were not able to buy nails then wood pegs would work. These pegs were not called "dowels" but rather "treenail, trunnel, or some variation of that term". When used to pull together a draw bore mortise and tenon joint they were quite effective. More useful is the fact that they could also be easily removed, as they were not glued, thus allowing larger pieces of furniture to be taken apart and moved upstair or across town, where they could be simply pegged back together again.

It was not really until ships began returning from overseas with more exotic timber than the usual domestic oak, walnut, cherry and beech. Harder woods, like ebony, would check and split when exposed to the climate of Europe. New methods were devised to saw these timbers into thin veneers, which could be then glued to a domestic substrate wood, combining the beauty of imported wood with the stability of air dried domestic timber.

These veneers, and the methods developed to apply them, created a new tradesman, the "ebeniste." This term was a direct reference to a woodworker who worked with ebony, and, as a logical extension, exotic wood sawn veneers. The golden age of ebenistes included such legends as Gole, Boulle, and Roubo. Without protein glues their craft would never have existed.

There are many different types of animal protein derived glues, and several varieties of each type are used for various specialized applications.

|

| Colle De Poisson or "Fish Glue" |

For example, fish glue is produced from different species of fish and different parts of each type of fish. Fish glue is normally liquid at room temperature and has a fairly long shelf life, at room temperature. You can expect it to remain useful for up to 5 years or more, depending on the quality of the glue. Fish glue is made and sold in Canada by Lee Valley and sold in the US by Norland Industries. Fish glue is what we use to hold brass, pewter, ivory, mother of pearl, horn, and other non wood materials to a wood substrate. Fish glue cleans up very easily with cold water. It also has a very low sheer resistance to creep, which allows the non metal elements of the surface to remain stuck as the wood substrate expands and contracts during environmental fluctuations. Toothing the metal (on the glue side) and rubbing the surface with a fresh clove of garlic prior to applying the glue is the traditional method.

|

| 192 Gram Hide Glue and Traditional Glue Pot |

Animal hide, connective tissue and ligaments, and animal bones are generally cooked until they become a glue. Hide glue is used by itself, bone glue is used by itself, and blends of the two are also used in woodworking, usually 1/3 bone to 2/3 hide. Hide glues are graded using a Bloom gelometer, which is an interesting tool. You should Google it and see for your self. It is important to note that these glues are sold in a "gram strength" number which ranges from around 50 to 500. The confusion is that people imagine the higher gram strength number indicates a stronger glue. This is false.

All grades of hide glue have adhesive strengths which are comparable. The difference is that the lower the gram strength the slower the glue sets and the more flexible the bond. The higher the gram strength the faster the glue sets and the more brittle the bond.

I buy all my protein hide glue from Milligan and Higgins. If you have questions, I encourage you to call them directly. Milligan and Higgins Use extension 18 to talk with Jay Utzig, my favorite glue chemist. If he is not fishing, then he is at work.

The use of a traditional double boiler glue pot is no longer in fashion. I use one in my shop, and have done so for nearly 50 years. I turn it on when I arrive and the last thing I do when I leave is turn it off. I have many videos on my YouTube channel ("3815utah") talking about using this glue, as well as the excellent videos posted on WoodTreks: Using Animal Protein Glue

|

| Processed Glue vrs Organic Glue |

When I researched methods to modify protein hide glues by lowering the gel point, I eventually developed a formula which I began selling as Old Brown Glue. It has been nearly 20 years that this glue has been available and the demand is growing exponentially. I knew that if the glue worked like I thought it did, then every woodworker who discovered it would tell two of his friends. By this method the word of mouth has created a demand that requires me to cook hundreds of pounds of glue each month. Lots of bottles, caps, labels, boxes, shipping labels, billing and so forth. Old Brown Glue has become a business on its own and has exceeded my modest expectations.

I have been asked by luthiers if Old Brown Glue would work for their instrument construction. I know that luthiers understand qualities of different glues better then furniture makers, and I believe that there is a real application for liquid glues, in addition to hot glues, depending on the project. Years ago I was approached by one of the most famous guitar makers in America. They wanted to test my glue to see if it would work in their production run. They were making a special 50th anniversary edition of their signature guitar and were instructed to use methods and materials which were as close as possible to the original. I sent them glue and they tested it for two years. Finally they decided it worked perfectly and began ordering a lot of glue.

I repeatedly called them to ask permission for posting on this blog, using their company name. I must say that the legal department of the guitar business is much more difficult to have a conversation with compared to the production line workers.

In any event, no response. Thus, in trying to avoid any direct legal conflict, I will merely post this YouTube video, which I found online: Guitar Factory Tour I think you will be interested in the glue used at the 2 minute mark. I would also like to post here one of my favorite guitars:

|

| Favorite Guitar Patent |

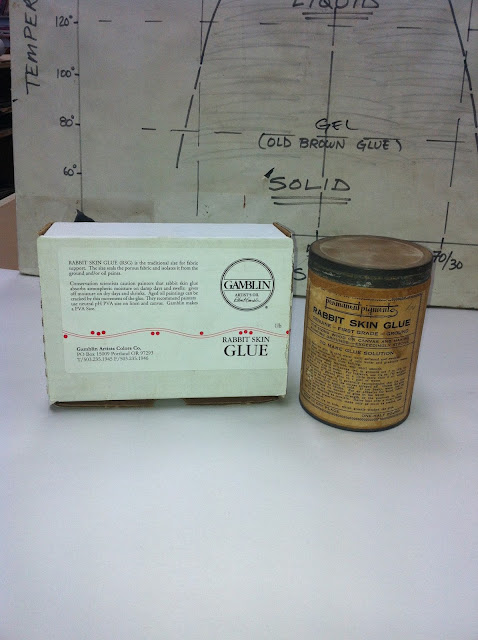

There is another type of protein glue, rabbit skin glue.

|

| Rabbit Skin Glue |

I created this simple chart for understanding protein glue:

|

| Temperature vrs. Humidity |

Hide glues and their working characteristics are a function of temperature and hydration. Dry glues are first hydrated with cold water, approximately 50/50. The better quality the glue the faster it will absorb the water. Then the hydrated glue is heated to around 140 degrees where it becomes liquid. Glue can be heated and cooled as many times as you want, as long as the temperature does not exceed 180 degrees.

Animal hide glue, both Old Brown Glue and Hot Hide Glue, is unique in that it can be in various states (solid, gel, liquid) without damaging the quality of the glue. It can be repeatedly frozen, thawed, heated, cooled and so forth as many times as you want, as long as it doesn't get moldy or heated to the boiling point. The same process used to mix it (add cold water and then heat) reverses to cure it (loss of heat and then loss of moisture.)

The rapid loss of heat in hot glue makes it perfect for a fast tack. Then, more gradually, it looses moisture into the wood and into the environment, for a full cure. Old Brown Glue takes much longer to tack, so it has a much longer open time. It then cures more slowly as it looses moisture much more slowly, achieving a full cure in a matter of a few days. Both types of glue create an equally strong bond.

Why not try some of my Old Brown Glue today? After all, I make it fresh every day. I will leave you this email, one of many such emails I receive every day from satisfied users of OBG. I asked Dave for his permission to copy this message. He said it would be fine with him.

Hi

I came across your glue whilst researching how to build a cigar box violin. I had made plenty of cigar box guitars but a violin was a whole new challenge so required lots of research and reading. I saw many articles mention hide glue as being the way to go for musical instruments because of the potential to reverse the glued joint without damage to the wood so I looked in my local store to see if they carried any - I knew Titebond did a hide glue, I had seen it on a TV show once and figured a big store would carry it. Fortunately, as it turns out, they did not.

More reading made me think twice about their version, seems it has extra additives and is not as simple and 'traditional' as your product. Thankfully my local Woodcraft store carries OBG so I picked up a small bottle.

I played around with it on a few test samples and very much liked the grab I got from just a plain rubbed joint with no clamping at all, a couple of days later the bond seemed very strong.

So I used it exclusively on the construction of my first ever cigar box violin. Much to my pleasant surprise this instrument actually played pretty well - I am no violin player but it made a good strong sound and stayed in tune quite well.

However after sharing some video of me playing it on a fiddle forum and reading more articles I came to the conclusion that the angle of the neck/fingerboard was wrong and the 'action' (the height of the strings above the fingerboard) was too high at the end near the body. If I had used regular white woodglue this would have been un-repairable and I would just have to have put up with it and learned a lesson for my next build. Because I had used OBG however I figured I would have a go at fixing this. I wrapped the body of the fiddle in a plastic bag to make sure I did not loosen any glued joints there, set up a small pan on a simple electric ring my wife uses for cooking her plant dyes and got the water boiling away. I held the neck of the violin over this and moved it back and forth for about ten minutes, then applied some very gentle pressure between the fingerboard and the neck using the handle of a metal knife. The end of the fingerboard nearest the body immediately separated a fraction of an inch away from the neck so I held it open and let the steam play in the crack. A couple more minutes and a little more gentle pressure and suddenly the whole fingerboard popped right off. There was no damage at all to either glued surface and only a couple of very small flakes of glue sticking up which sanded right off very some very fine paper. Since I understand that your glue will stick to itself I do not even need to worry about trying to clean up the surfaces before gluing anything else to them. I made a long thin wedge which I have now glued to the neck, that should be dry enough today for me to glue the fingerboard to it and the repair will be complete!

So I shall be using your glue for many more projects (where it is appropriate) and recommending it to anyone else I talk to. I love the nature of the product and the way your business works and wish you all the best of success.

Many thanks

Dave Perks (Sacramento Ca)

This Just In! It seems that Popular Woodworking magazine is out with an informative article by Christopher Schwarz called "The Best Glue for Furniture?" He discusses liquid glue and you can either pick up a copy or click here for a taste: Popular Woodworking Magazine: Glue

Friday, January 13, 2017

Carpenters, Electricians or Plumbers?

I have quite a few clients who are doctors. Now that I think of it I also have had quite a few doctors as students. Years ago (many years ago) I taught a series of classes on Decorative Arts at my alma mater, U.C.S.D. In one of these classes I had a distinguished looking gentleman who always sat in the front row, directly in front of me, and asked very intelligent questions. After several lectures, I asked him who he was and he responded, "I'm Dr. U". It impressed me, since he confirmed that his last name was the singular letter "U". I asked him what kind of doctor he was and he replied "brain surgeon."

As my degree was in High Energy Particle Physics, I thought this was interesting. I can see the headlines now: "Rocket Scientist teaches Brain Surgeon."

In conversation after class, I asked him why he would take the time to sit through my lectures, as he must be rather busy with his profession. He complimented me very much when he simply replied, "You are a good teacher."

Some years later I noted in the news that a difficult medical case had been treated at UCSD Medical Center, where a tumor was removed from a patient's brain in a 23 hour procedure. The doctor who stood in one position for 23 hours and patiently cut away the tumor, stitching each vessel with 10 microscopic stitches was Dr. U.

When I taught my first class at Marc Adams School of Woodworking I had the school make 8 chevalets, and I thought they would be in different sizes. However, they made them all the same size, 61cm tall, which would be perfect if the student was 6'2". Naturally all the students were different heights, so I had to make risers for the seats. In that first class I had a very enthusiastic woman who was 4' 11" tall. Her name was Pepper and she was a medical doctor. Doctor Pepper. She was an exceptional worker and impressed me with her attitude. Out of the 8 students 3 were medical doctors and one was a medical nurse.

At some point (I can't remember who or where) I had a client who was a doctor tell me that "We're all either carpenters, electricians or plumbers." I thought that was a rather humble description of one of the most important professions on earth. "Carpenters" fix broken bones, "Electricians" repair damaged nerves and "plumbers" solve leaky pipes. (I don't want to be more specific...)

If I had entered the medical profession I would be a good doctor. I would be a "Carpenter" since I understand how to repair structural damage, with the least invasive methods. When I fix something it is fixed. I spend a lot of my work repairing the damage caused not only by the accident but also (and much worse) the damage caused by amateur attempts to repair it, before it was brought to me.

I have posted before about Vector Clamping. It is my way of teaching about proper methods of applying pressure on a glue joint. When the joint is straight and even and the clamping surface is parallel to the joint, it is obvious where to clamp. However, when the repair involves complicated curves and many different breaks it becomes more difficult to visualize where to apply the clamps.

This is where amateur woodworkers get in trouble. Either they don't have enough clamps or the proper clamps, or the proper glue, or they try to just flood the break with glue, thinking it will fill all the gaps. In any case, the repair is usually horrible. By understanding Vector Clamping theory the repair will be easy, and the minimum number of clamps will be needed.

Vector Clamping means that a single clamp must be applied in the center of the joint and perpendicular to its surface. On curves this means an additional scrap piece of material must be attached temporarily to properly provide a place for the main clamp to do its work.

Repairing a curved leg on a tripod table is a good example. This nice early table came in last week with a broken leg. An effort to repair it involved a large dowel going sideways, lots of yellow glue and a lot of missing wood. The person who had attempted to repair it had damaged much of the surface of the joint so that it was no longer useable.

I used a toothing plane to clean up the glue residue. You must glue to clean wood. You cannot glue to dirt, old glue (unless it is a protein glue), or any other contaminant. The success of the repair depends on the wood to wood surface contact. This is why dowels are not as good as tenons. Dowels present a circular surface which contacts as much end grain as side grain. Tenons contact a larger area of side grain than end grain, so are stronger.

To begin the repair I fashioned pine clamping jigs, which are attached to the leg and foot. If you study the photo you will see only two of the clamps do the actual work on the repair. The vertical center clamp holds the piece in position while the diagonal clamp (on the back of the leg, difficult to see) is pulling the foot towards the leg. The rest of the clamps are used to hold the jigs.

I used a pattern to determine the shape of the new piece. In this case I used a piece of recycled Cuban mahogany, as the table was made in that wood. Note the tenon extension I provided which fit into the foot element, as there was not enough end grain on the foot piece to guarantee strength.

This shows the repair after the clamps were removed:

Looking at the leg from the end to be sure it was straight:

A second piece of mahogany was added to the bottom of the leg for extra strength across the weakest part of the repair:

This is the repair before finishing:

I actually don't like the term "Carpenter". I am not a "Carpenter". Carpenters build houses and use nails to fasten wood together. For the purposes of this post I will not complain. It is a metaphor.

I am a Problem Solver.

As my degree was in High Energy Particle Physics, I thought this was interesting. I can see the headlines now: "Rocket Scientist teaches Brain Surgeon."

In conversation after class, I asked him why he would take the time to sit through my lectures, as he must be rather busy with his profession. He complimented me very much when he simply replied, "You are a good teacher."

Some years later I noted in the news that a difficult medical case had been treated at UCSD Medical Center, where a tumor was removed from a patient's brain in a 23 hour procedure. The doctor who stood in one position for 23 hours and patiently cut away the tumor, stitching each vessel with 10 microscopic stitches was Dr. U.

When I taught my first class at Marc Adams School of Woodworking I had the school make 8 chevalets, and I thought they would be in different sizes. However, they made them all the same size, 61cm tall, which would be perfect if the student was 6'2". Naturally all the students were different heights, so I had to make risers for the seats. In that first class I had a very enthusiastic woman who was 4' 11" tall. Her name was Pepper and she was a medical doctor. Doctor Pepper. She was an exceptional worker and impressed me with her attitude. Out of the 8 students 3 were medical doctors and one was a medical nurse.

At some point (I can't remember who or where) I had a client who was a doctor tell me that "We're all either carpenters, electricians or plumbers." I thought that was a rather humble description of one of the most important professions on earth. "Carpenters" fix broken bones, "Electricians" repair damaged nerves and "plumbers" solve leaky pipes. (I don't want to be more specific...)

If I had entered the medical profession I would be a good doctor. I would be a "Carpenter" since I understand how to repair structural damage, with the least invasive methods. When I fix something it is fixed. I spend a lot of my work repairing the damage caused not only by the accident but also (and much worse) the damage caused by amateur attempts to repair it, before it was brought to me.

I have posted before about Vector Clamping. It is my way of teaching about proper methods of applying pressure on a glue joint. When the joint is straight and even and the clamping surface is parallel to the joint, it is obvious where to clamp. However, when the repair involves complicated curves and many different breaks it becomes more difficult to visualize where to apply the clamps.

This is where amateur woodworkers get in trouble. Either they don't have enough clamps or the proper clamps, or the proper glue, or they try to just flood the break with glue, thinking it will fill all the gaps. In any case, the repair is usually horrible. By understanding Vector Clamping theory the repair will be easy, and the minimum number of clamps will be needed.

Vector Clamping means that a single clamp must be applied in the center of the joint and perpendicular to its surface. On curves this means an additional scrap piece of material must be attached temporarily to properly provide a place for the main clamp to do its work.

Repairing a curved leg on a tripod table is a good example. This nice early table came in last week with a broken leg. An effort to repair it involved a large dowel going sideways, lots of yellow glue and a lot of missing wood. The person who had attempted to repair it had damaged much of the surface of the joint so that it was no longer useable.

I used a toothing plane to clean up the glue residue. You must glue to clean wood. You cannot glue to dirt, old glue (unless it is a protein glue), or any other contaminant. The success of the repair depends on the wood to wood surface contact. This is why dowels are not as good as tenons. Dowels present a circular surface which contacts as much end grain as side grain. Tenons contact a larger area of side grain than end grain, so are stronger.

To begin the repair I fashioned pine clamping jigs, which are attached to the leg and foot. If you study the photo you will see only two of the clamps do the actual work on the repair. The vertical center clamp holds the piece in position while the diagonal clamp (on the back of the leg, difficult to see) is pulling the foot towards the leg. The rest of the clamps are used to hold the jigs.

|

| Wood Elements Added for Vector Clamping |

I used a pattern to determine the shape of the new piece. In this case I used a piece of recycled Cuban mahogany, as the table was made in that wood. Note the tenon extension I provided which fit into the foot element, as there was not enough end grain on the foot piece to guarantee strength.

|

| Foot on Left Photo, Leg on Right Side, Pattern for Repair |

This shows the repair after the clamps were removed:

|

| Cuban Mahogany Element Before Shaping |

|

| Looks Straight To Me |

|

| Second Piece of Mahogany Added to Bottom of Leg |

|

| Note The Curve Is Continuous and Smooth |

I am a Problem Solver.

Friday, January 6, 2017

Antique Furniture Forensics

One of the reasons that antique furniture is less and less appreciated these days is that few people are left in the business who are "experts" with real "experience" in the field.

40 years ago, when I travelled the country, stopping in every antique shop I could find in every town, I would usually find a dealer in the shop who was an expert in something. It might be porcelain, silver, art, carpets, books, tools or furniture. I learned a great deal from those dealers. They would take the time to explain as much as they knew about what they were selling.

As I gathered data on the regional characteristics of American 19th century furniture, I would pointedly ask "what furniture do you have in the store which was made locally and what features can you identify that prove your theory?" I gained a real understanding of what made Texan furniture different from Tennessee or Connecticut from Ohio. Everywhere I went was an education.

A terrible transformation occurred over the next few decades, as individual dealers either retired or closed their stores, due to less demand and more expensive overhead. What took the place of the owner operated stand alone antique store was the "antique mall." This new marketing venue was a direct result of the success of yard sales and flea markets, where less knowledgeble sellers would offer items of unknown origin to bargain hunters. Each mall was managed by a single person at the front, and walking through these "stores" was as miserable and disappointing as you might think.

Each seller would rent a stall and fill it with junk. After all, it was cheaper than renting a storage unit, and there was always the possibility that someone would want to buy something. If you, as a shopper, found something interesting you would take it to the front desk and make the purchase. The manager or sales clerk knew absolutely nothing about the item. Only which stall and how much.

There was no possibility of learning anything.

Over time, even these pitiful excuses for antique stores became obsolete. They have been replaced by online sites like Craig's list and eBay.

Antique buyers need help. I have always believed in educating clients and prospective collectors about the process of understanding how early hand made (pre industrial) furniture was made. One of the methods is to have lectures, with examples that students can examine and touch.

For over 30 years I have been associated with Nancy Martin, ASA. Her career began in science, as did mine, and we think alike. Always looking for evidence, details and facts which can be used to identify the specific origin of an objects. Looking at tool marks, construction features, wood analysis, hardware, and other materials provides the best basis for determining the origin. It can be a fake, a reproduction, or an antique that is original or repaired. It is not always obvious but careful examination will ultimately provide sufficient evidence to indicate the proper date and origin.

Next month I will again be sharing the podium with Nancy Martin. We are jointly teaching an ASA class for appraisers at the Huntington Library in San Marino. ASA members as well as non-members are welcome. Here is the link: Antique Furniture Authentication Presentation

If you are in the Southern California region and wish to learn more about antique furniture in a wonderful environment, send in your reservation. I hope to see you there.

I guarantee you will learn something useful.

40 years ago, when I travelled the country, stopping in every antique shop I could find in every town, I would usually find a dealer in the shop who was an expert in something. It might be porcelain, silver, art, carpets, books, tools or furniture. I learned a great deal from those dealers. They would take the time to explain as much as they knew about what they were selling.

As I gathered data on the regional characteristics of American 19th century furniture, I would pointedly ask "what furniture do you have in the store which was made locally and what features can you identify that prove your theory?" I gained a real understanding of what made Texan furniture different from Tennessee or Connecticut from Ohio. Everywhere I went was an education.

A terrible transformation occurred over the next few decades, as individual dealers either retired or closed their stores, due to less demand and more expensive overhead. What took the place of the owner operated stand alone antique store was the "antique mall." This new marketing venue was a direct result of the success of yard sales and flea markets, where less knowledgeble sellers would offer items of unknown origin to bargain hunters. Each mall was managed by a single person at the front, and walking through these "stores" was as miserable and disappointing as you might think.

Each seller would rent a stall and fill it with junk. After all, it was cheaper than renting a storage unit, and there was always the possibility that someone would want to buy something. If you, as a shopper, found something interesting you would take it to the front desk and make the purchase. The manager or sales clerk knew absolutely nothing about the item. Only which stall and how much.

There was no possibility of learning anything.

Over time, even these pitiful excuses for antique stores became obsolete. They have been replaced by online sites like Craig's list and eBay.

Antique buyers need help. I have always believed in educating clients and prospective collectors about the process of understanding how early hand made (pre industrial) furniture was made. One of the methods is to have lectures, with examples that students can examine and touch.

For over 30 years I have been associated with Nancy Martin, ASA. Her career began in science, as did mine, and we think alike. Always looking for evidence, details and facts which can be used to identify the specific origin of an objects. Looking at tool marks, construction features, wood analysis, hardware, and other materials provides the best basis for determining the origin. It can be a fake, a reproduction, or an antique that is original or repaired. It is not always obvious but careful examination will ultimately provide sufficient evidence to indicate the proper date and origin.

Next month I will again be sharing the podium with Nancy Martin. We are jointly teaching an ASA class for appraisers at the Huntington Library in San Marino. ASA members as well as non-members are welcome. Here is the link: Antique Furniture Authentication Presentation

If you are in the Southern California region and wish to learn more about antique furniture in a wonderful environment, send in your reservation. I hope to see you there.

I guarantee you will learn something useful.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)