Fortunately, I had decided to arrive several days in advance of the WIA conference and stay a few days after, so Kristen and I were able to spend some quality time in old Winston Salem. In fact, the last time I visited Winston Salem and MESDA was in 1978, during one of my several trips to visit East coast museums and historic settlements. I am sorry it took so long for me to return.

The weather was great, in fact, with only a slight spot of rain and moderate heat. While I was away, on the other hand, San Diego had a heat wave, with several days above 100 degrees. Poor Patrice had to work at the bench, building the top of our Treasure Box (Series 2) while I got to wander around from place to place, thinking perhaps I should have packed a sweater.

Last year, during this time, I was teaching at Marc Adams school, and only had a short time late on Saturday to get away. I broke several speed limits driving from the school to Cincinnati to see the WIA event. I got there about 30 minutes before it closed, with just enough time to get my signed copies of Roubo from Chris. As it turned out, I also had to sign a few copies, since I wrote the Forward. The best part was that I got to have a nice dinner with Roy later that evening.

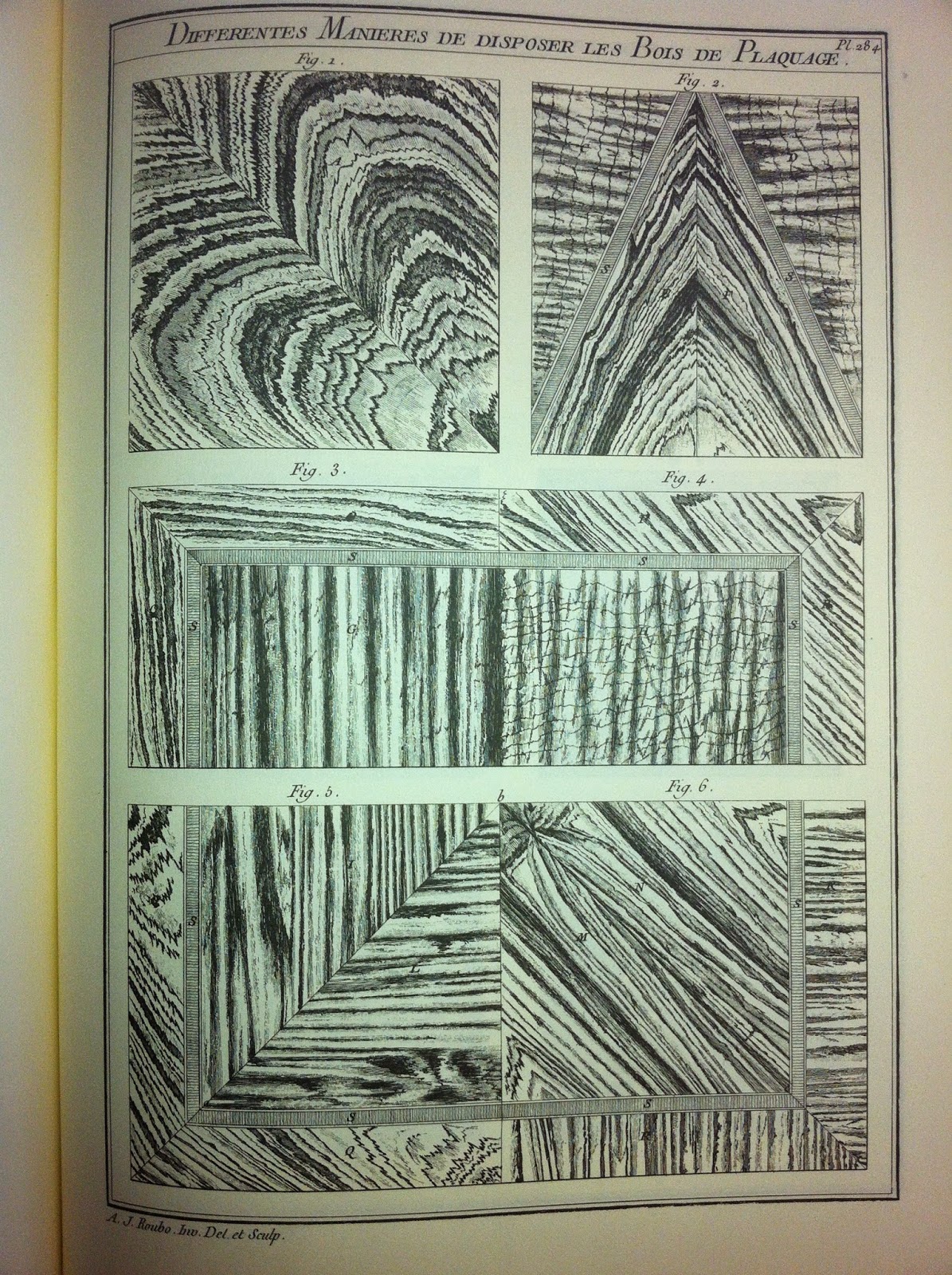

This year, I was a speaker, and presented two lectures to a rather enthusiastic and supportive audience. The first was a talk on "Historic Marquetry Procedures,"and went through basically 500 years of the traditional methods used to create this art form. The second was "Building and Using a Chevalet." At the start of this lecture, I mentioned that I have been working for nearly 20 years to introduce this unique tool to woodworkers in North America. Then I foolishly asked if anyone in the audience knew about this tool. When nobody raised their hand, a person in the back shouted, "You haven't been very successful!" As they always say in law school, "Never ask a question if you don't already know the answer."

I shared the lecture room with Roy Underhill, which is always an experience. As I was setting up my talk, he was putting his things away. They had scheduled a half hour break between speakers. Just about the time I was ready to start, Roy had the brilliant idea to "introduce" me. You probably already know he can be theatrical, to say the least.

He said the first time we met was at the Great Salt Lake, and there was a stampede of brine shrimp. Tim Webster was sitting in the audience, and had the quick thinking to pull out his camera and video it, posting it on YouTube soon after. I was speechless and had to hold my tongue, while he went on and on, creating a story that was more and more amazing. My mike was turned up to the max and when I did comment it was way too loud. Near the end I asked him to turn down the mike, and he crawled under the screen to adjust the volume. I thought I had a quick wit, but there is no way I can keep up with Roy when he is "on."

Here is the video: Underhill introducing Edwards

While I was having fun in the lecture hall, Kristen was in the Trade Show, where we had a booth for both the ASFM school and OBG. She is a master of working these shows, and I am very grateful for her talent, as I usually lose my voice and patience trying to compete with the noise.

Of course, Roy had to stop by and pick up some glue...

At the end of the show, they gave away a rather expensive band saw. I wondered if it would fit in the overhead compartment on the plane, but fortunately I was not in the contest to win it. However, they asked all the speakers at the show to sign it. I asked, rather incredulously, if they really want me to sign a power tool? They insisted, so I did. You can see my name, with the comment added

"Use hand tools."

After the show Kristen and I went to MESDA where we had a nice tour with Daniel Ackerman. We also enjoyed a private home tour by Tom Sears, both of which are members of SAPFM. We had dinner with Jerome Bias, who is the joiner at Old Salem, and then visited him at work, where he demonstrated his Roubo veneer saw.

Across the hall Brian Coe was using the foot power lathe to make some turnings. That is a rather impressive tool, made from massive pieces of oak.

All of this activity was in the Brothers House, and it was full of woodworkers from the show, having a great time sharing stories. There was a warm sense of camaraderie and mutual friendship.

I made a promise to myself not to wait another 30 years before returning to Winston Salem. Thanks to Megan, Don, Roy, Jerome, Daniel, Phil, Freddy, Martin, Tom, Brian, Will, and too many others to name. You know who you are!